Unless you have been living under a rock, you are undoubtedly familiar with the latest collectible craze hijacking your TikTok and Instagram feeds: the Stanley cup.

It may be just a water bottle with a removeable straw and a side handle, but these steel tumblers that come in a variety of sizes and colors and cost between $35 and $50 have been flying off the shelves of Target and Starbucks. Reports of people camping out overnight or getting in fights while jockeying for space in line when a new tumbler drops maintain a steady stream on social media.

The baffling trend cemented its status as a pop culture phenomenon when it was featured in a recent Saturday Night Live skit featuring Dakota Johnson, “Big Dumb Cups.”

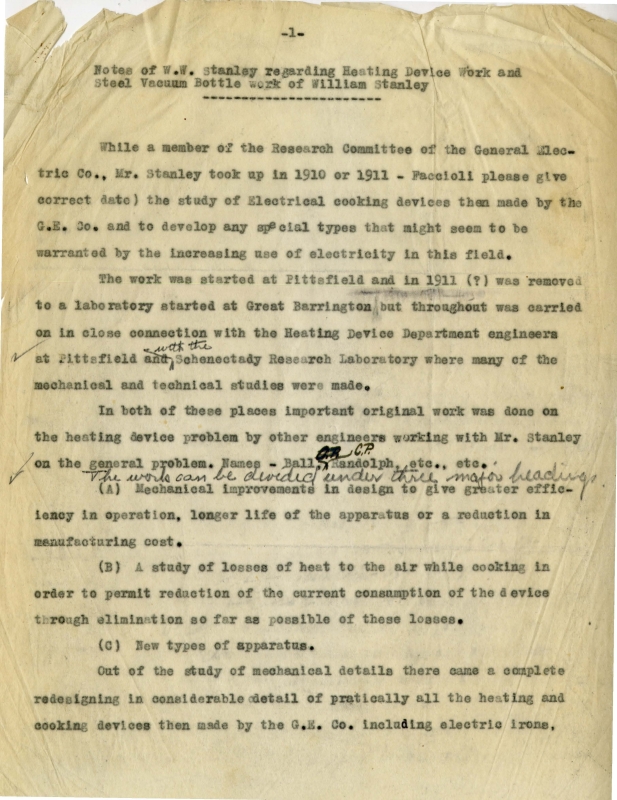

Yet few are aware of the connection between Union and the prolific inventor behind the cup’s technology, William Stanley Jr. For 40 years, the College has hosted the most extensive collection of Stanley’s papers. The collection was gifted to the College in 1984 after the Stanley Library at General Electric in Pittsfield, Mass., closed. At the time, Union had established the Schenectady Archives of Science and Technology at Schaffer Library, as a place for the papers of notable scientists and engineers to assist researchers.

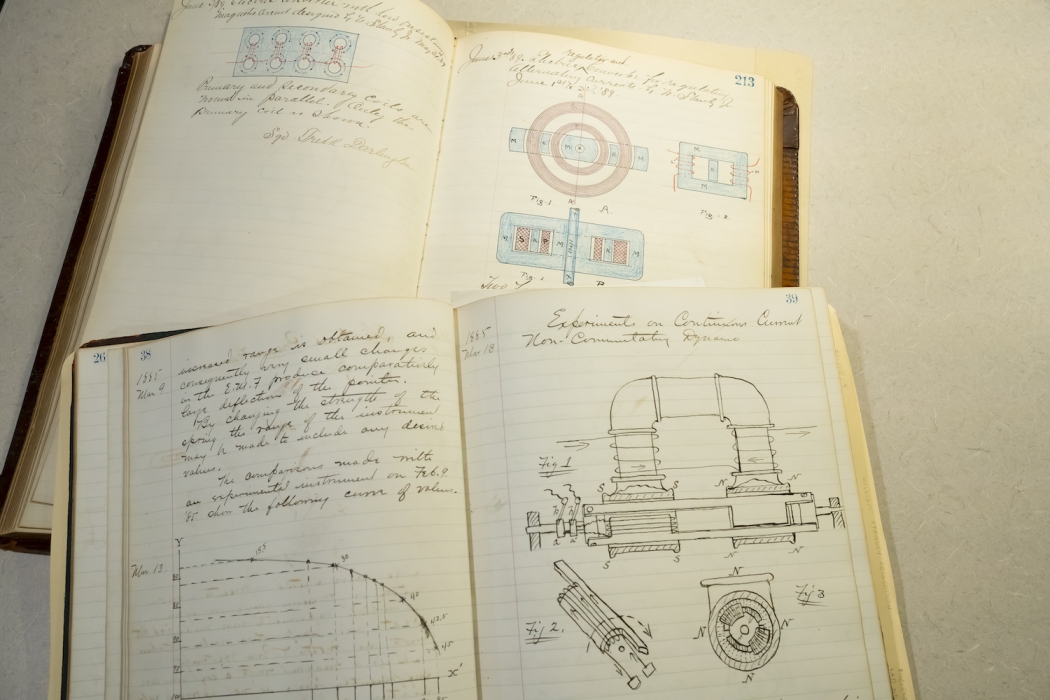

The Stanley collection includes 19 boxes stuffed with laboratory notebooks, original drawings, printed ephemera and more, primarily covering the years 1882 until Stanley’s death in 1916.

Most of the material focuses on Stanley’s legacy as an electric pioneer, working with the likes of George Westinghouse (who briefly attended Union in 1865) and others. A self-taught engineer and the holder of more than 100 patents, Stanley is credited with perfecting the first electrical transformer and establishing an alternating current system that led to widespread electricity use.

It was Stanley’s experiments with electric ranges, insulation and thermal conductivity that laid the groundwork for the Stanley tumblers favored mostly by millennial and Gen Z women today.

“Rumor has it, that he wanted his coffee hot all day while he was working, and was inspired to apply some of his theories learned while developing transformers,” according to the Stanley company history.

Working in his lab in Great Barrington, Mass., in 1913, Stanley designed the first all-steel, double-walled, vacuum sealed bottle. Earlier models of a thermos included a metal exterior and a glass interior, which cooled things fast and shattered easily.

Temi Olasubomi ’26, Ashley German Soto ’24 and Niamaya Canady, assistant director of Intercultural Affairs, with their Stanleys.

Of his new invention, Stanley said “these bottles not only possess remarkable thermal properties, but as they are made of steel are practically indestructible,” according to “William Stanley Lighted a Town and Powered an Industry,” published by the Berkshire County Historical Society.

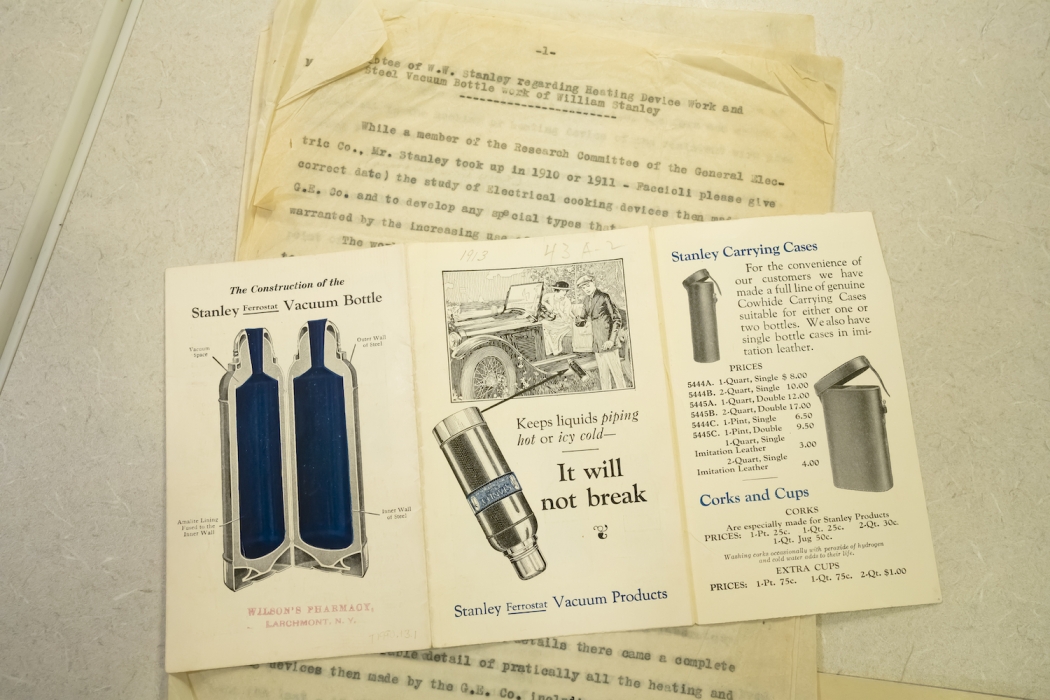

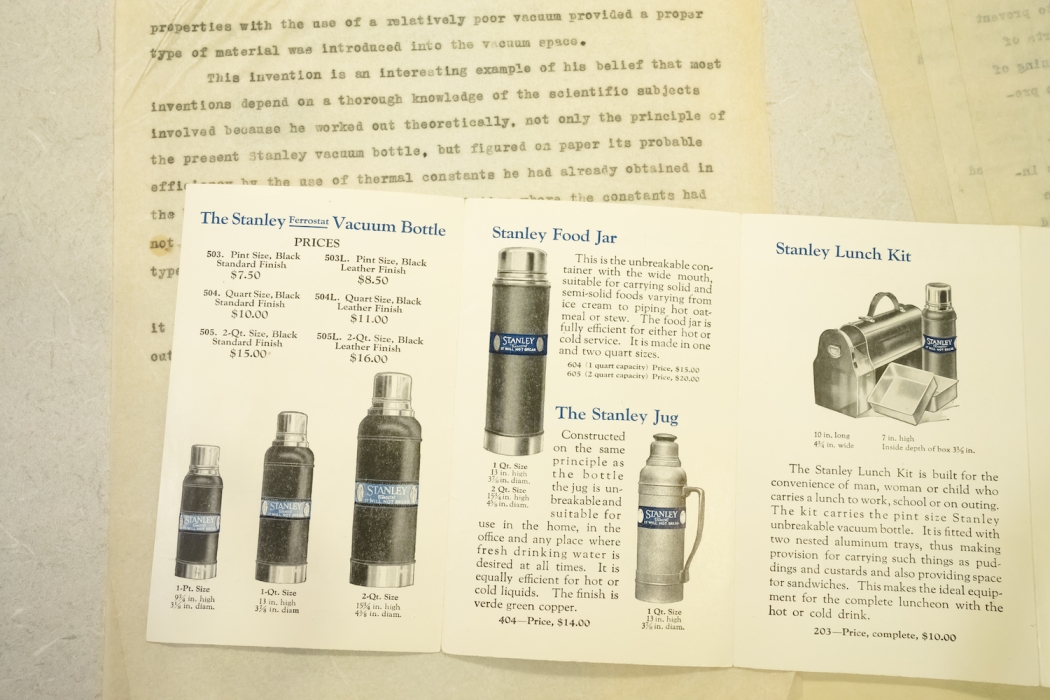

A year before his death, Stanley created a new company, Stanley Insulating Co., to manufacture his latest creation. Early brochures of the company’s product line are included in the Stanley collection, featuring the vacuum bottle, a food jar and a lunch kit, all promising to keep its contents “piping hot or icy cold.”

For most of its more than 100 years in existence, the company, now simply called Stanley and based in Seattle, targeted outdoorsmen and blue-collar workers thirsty for a durable flask. A few years ago, the company made a brilliant calculation, tapping into the power of influencers with a huge female following, turning its Quencher model into the latest trend.

Take a random stroll through the Reamer Campus Center, the Wold Center or the Integrated Science and Engineering Complex, and Stanleys are nearly as common as laptops.

Ashley German Soto ’24 loves her 40-ounce tumbler. She got it in December. She now owns two Stanleys.

“I can mix and match them to wear with my outfits,” said German Soto, a political science major from Boston.

Temi Olasubomi ’26 bought her 30-ounce pink Stanley last month

“She’s so cute,” said Olasubomi, a computer science major from Bear, Del. “She keeps my water very cold.”

Meanwhile, in Special Collections, Corrine Chatnik, digital collections and preservation librarian, and Becky Fried, digital projects and metadata librarian, are leading an effort to digitize the Stanley collection to make it more accessible to the public.

Matthew Gołębiewski, processing and records management librarian, hopes the current cup craze will lead to Stanley getting the recognition he deserves for the development of the alternating current transformer. Though he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1995, Stanley’s story is not as widely known as other major figures of his time, including Westinghouse, Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla.

“Stanley is seen as a footnote compared to others of his time,” said Gołębiewski. “The Stanley papers are a pretty significant collection, and once it is digitized, it should attract widespread interest from researchers.”

Early brochures of the company’s product line are included in the William Stanley Jr. collection housed in Special Collections.