Fall of 1968. The Vietnam War continues to escalate and student unrest swells on college campuses. Months earlier, the Rev. Martin Luther King and Senator Robert E. Kennedy had been assassinated.

Political Forum wants a dynamic speaker who represents a point of view that will deliver a jolt to a campus that feels a bit removed from the conflicts of the time.

Abbott Stillman, president of the group founded a decade earlier at Union to “promote political interest on campus,” sets his sights on the charismatic, controversial 26-year-old former heavyweight champion, Muhammad Ali.

Ali had recently been stripped of his boxing title when, as a Muslim, he refused induction into the Army ("War is against the teachings of the Koran," he said. "I'm not trying to dodge the draft [but] we don't take part in Christian wars.”).

Convicted of violating Selective Service laws, Ali is sentenced to the maximum five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. He is free on bail pending an appeal.

Barred from making a living as a boxer, Ali embarks on a series of speaking engagements at colleges and universities. He is often greeted as a hero for his anti-war stance. Others call him a coward.

On Thursday, Oct. 24, 1968, Union is the second stop on the exiled fighter’s 68-college tour. Political Forum pays Ali the standard $3,000, plus dinner and a hotel room. They get their money’s worth and more.

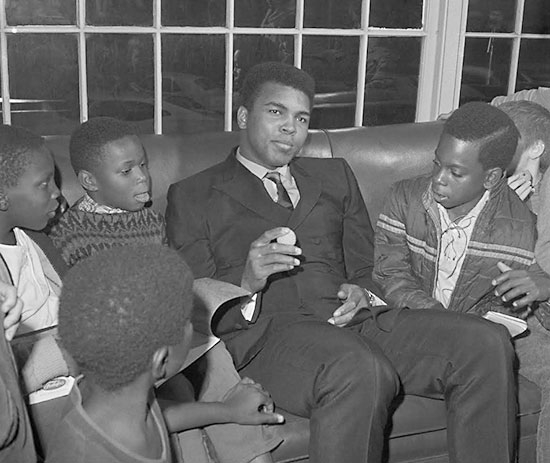

Before the talk, Stillman ‘69 invites Ali to dinner with his Phi Sigma Delta fraternity brothers at their house on Lenox Road. There, the man previously known as Cassius Clay regales them with stories of his life. Ever the showman, he shadow-boxes with some of the brothers. A group of giddy local fourth-graders adopted by the frat as “little brothers” watches in awe.

After dinner, Stillman walks with Ali to Memorial Chapel. He asks about some of his fights, including the two with Sonny Liston, the man Ali had beaten in 1964 to win the world heavyweight championship at 22. In their rematch, Ali knocked out Liston with what some believed was a “phantom punch” signaling the fight was fixed.

Stillman brings up the punch. Ali stops walking and directs the senior to stand beside him and carefully watch his hands. Ali then unleashes a blur of mock jabs and combinations. Stillman is convinced there was no phantom punch.

“He’s just a very special fighter who was so much faster than any big man had been before that people just couldn't believe what they'd seen,” Stillman recalls.

At Memorial Chapel, Ali is greeted by an overflow crowd. Dressed in a double-breasted silk gray suit, the boyishly handsome Ali spends nearly an hour entertaining the boisterous audience. At times angry, funny and always provocative, he shares his thoughts on a wide range of topics, from the teachings of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad to his relationship with his mentor, Malcolm X.

He also speaks of the tension between whites and blacks, and how blacks are conditioned to think “white.” He points out that Santa Claus is white. So is Jesus.

“Even Tarzan, king of the African jungle, is a white man swinging around each week with diapers on,” he says, referring to a popular television show at the time.

He offers a solution. It makes headlines the next day.

“We don’t hate white people – we know them too well,” he says. “And the only solution to today’s racial problems is separation.”

Each anecdote, joke or lesson is met with cheers and applause. Ali’s magnetism is infectious.

When the talk is over, the crowd rewards Ali with a standing ovation.

Always quick with a rhyme, Ali leaves his guests with a poem.

“I like your school and admire your style, but your pay is so small, I won't be back for a while.”

Fast forward nearly five decades. The champ is 73 now and suffering from the effects of Parkinson’s and other ailments. He spends most of his time in Arizona. Public appearances are rare. Interviews are scarce. The brash, cocky talker is now mostly muted.

But the memories made on campus 47 years ago still hold.

“Some people just have charisma,” Stillman said from his home in Scarsdale, N.Y. “This guy had so much that it seemed the air moved around him. He won over everyone in my fraternity, and all the others he met on campus, simply by his presence.”

Sports Illustrated recently announced that its annual sportsmanship award will be renamed in honor of Ali. The award is given to people who "embody the ideals of sportsmanship, leadership and philanthropy." The magazine says there is "no better example of this tradition of excellence and influence than Muhammad Ali."