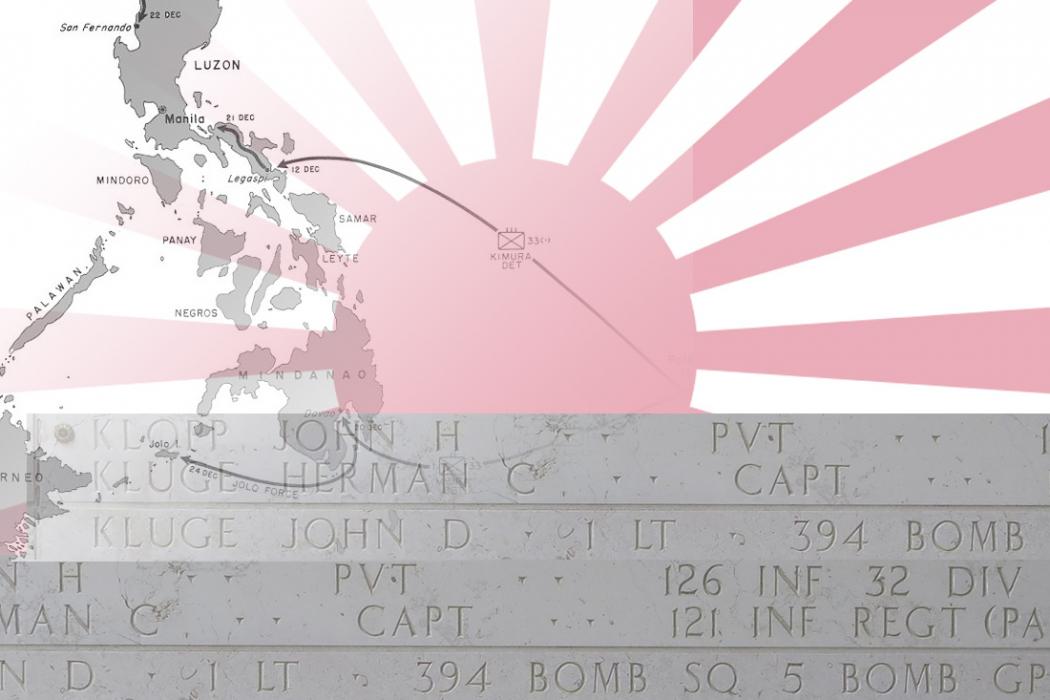

July 1943. The 60-year-old soldier is trapped. Japanese forces occupy the Philippines islands during World War II.

Captain Herman C. Kluge, a member of Union’s Class of 1905, is one of the leaders of tenacious American-commanded guerilla units battling the Japanese in the mountains of northern Luzon. The Japanese are familiar with Kluge. The guerillas are making life miserable for them with reconnaissance missions and frequent ambushes of their supply trucks along the trails. A bounty is placed on his head.

One night, on his way to a secret meeting with an American officer, Kluge wanders into a Japanese encampment. Some villagers shield him for a brief period, but eventually two Filipinos betray his location to the Japanese.

Word reaches Kluge: Surrender or the Japanese will begin slaughtering woman and children and burn the village.

Kluge knows what he must do. He comes down from the hills and into enemy captivity.

What happens next is unclear. Japan’s response to the resistance efforts is brutal. Conflicting reports say Kluge is executed as a warning to Filipinos siding with the Americans. (The Philippines is a U.S. commonwealth, and Filipinos are U.S. nationals.) Or that he is sent to a prison camp and tortured for months before he is ordered to dig his own grave and buried alive.

Whatever Kluge’s unspeakable fate, his remains are never recovered.

Kluge’s story is one of the most exceptional of the thousands of Union alumni with military experience. Yet few today are familiar with his heroism.

As John Graham Dowling, a war correspondent for the Chicago Sun Foreign Service traveling with the guerrillas observed in this dispatch at the time:

“They tell you about Herman Kluge, ‘Herman the German,’ Old Clock Eye.” He spoke 10 languages and graduated from Union College, New York. If you think a man becomes a legend for nothing, listen further to the way he finished when finally the Japs had his hiding place in the hills spotted.

“It would have been easy for Old Clock Eye to get away, just down the side of one mountain and up the next. But he knew the Japs would just as soon kill the natives as look at them. Sooner, perhaps. All they needed was an excuse. So he came down the hill and surrendered. He died shortly afterward in a Jap concentration camp. But before he died, he had won even the respect of his captors. Thus, Herman Kluge.”

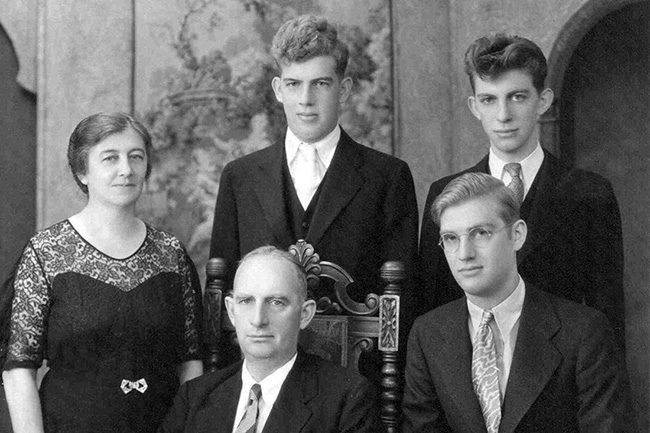

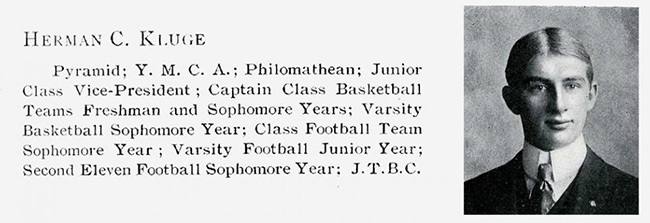

Kluge arrives at Union in September 1901 from Elmira, N.Y. Vice president of his class, he letters in football and basketball. He joins the Pyramid Club, a new social group for non-fraternity men. He graduates with a degree in civil engineering.

Five years after leaving Union, Kluge marries a Schenectady girl, Anna Dettbarn. The couple travel to some of the farthest parts of the world as Kluge becomes a successful lumber mill cruiser, scouting out potential lumbering sites.

“We think that Herman C. Kluge has visited more out of the way places than any living Union man,” a class note mentions in the alumni monthly in 1921. “His work as a lumber expert and engineer has taken him to most of the West Indies Islands, countries of Central America, as well as England, France, Spain, Portugal and South American countries.”

The Kluges settle in Englewood, Fla., but when the Great Depression erases their savings, Herman accepts a job in the Philippines as superintendent of the world’s largest hardwood sawmill.

Still, the couple returns often to the Schenectady area. Two of their three sons graduate from Union - Herman D. Kluge in 1936 and August Kluge in 1940.

“Glad you sent me a line to this place,” he writes to the alumni office in 1933. “You know that this little cockeyed world of ours has some queer places that are mentioned in the National Geographic…”

Early 1941. Kluge oversees a handful of sawmills in the Philippines. A Japanese invasion is imminent.

“Every once in a while my attention is drawn to Old Union,” he writes to the alumni office in January. He shares a meeting with a Colgate alumnus, Col. John P. Horan that might be worthy of a class note, even suggesting the headline, ‘Union meets Colgate.’ He’s happy to have a radio to keep up on news as world tensions increase.

“We out here are all for the President and his methods of procedure and hope that he will receive the wholehearted backing of the American people,” he writes.

Charles Waldron '06, secretary of the Graduate Council, maintains regular correspondence with Kluge.

“I am glad you feel the President’s foreign policy is sound,” Waldron replies. “I fairly boil over when I think of the fatheads in this country who believe that we can forget the rest of the world and pretend we do not live in it.”

By November, Kluge informs Waldron that “it looks like we will have news soon for war is coming to the Far East. Not that we are ready for it but out here among the people who know, the consensus of opinion is that we have the Japs to lick and the sooner we get at it the better.”

When the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor, Herman and Anna decide to flee. They load food, a radio battery and clothing into their station wagon and head north to an Episcopal compound at Sagada.

“My thoughts are very much with you men in the Philippine Islands,” Waldron writes to Kluge. “I do not know if this note will reach you. We watch with anxiety and pride the fight you are putting up. You, I know, will be resourceful and very brave. I wish there were many more like you.”

The note is returned to sender.

In mid-January, Col. Horan returns for a surprise visit with Kluge. Under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Horan is organizing guerrilla units to slow the Japanese march across the islands. Familiar with Kluge’s background serving with the intelligence department during World War I and his knowledge of the Japanese language, Horan recruits Kluge to join the resistance.

During one crucial battle over a stretch of 8,000-foot mountains, Kluge and a handful of guerrillas, 18 Philippine Scouts and 12 Chinese volunteers armed with rifles, pistols and shotguns hold off nearly 400 Japanese armed with machine guns, mortars and mountain artillery.

In the spring, the combined regular American-Filipino army suffers a key defeat at the Battle of Corregidor. But the guerillas fight on. In June, Kluge reunites briefly with Anna. Kneeling at a small altar, they share communion from a Catholic priest together.

“Children, this may be the last time you will see each other,” the priest solemnly tells them.

Kluge returns to his unit, which continues to torment the Japanese. Meanwhile, Anna escapes into the woods with two women missionaries.

By June 1943, the Japanese are in firm control of the Philippines. Kluge hikes to try and meet with Col. Russell Volckmann, who has taken over the guerrilla forces in the mountains of North Luzon.

He reaches the province of Benguet. He finds himself surrounded by the Japanese. Villagers call him Apo (“good old friend). They hide him and sneak him food. But the Japanese offer of 5,000 pesos ($2,500) for his capture proves tempting for two Filipinos.

Kluge surrenders. It is July 4, 1943.

Guerrillas Rescue Two U.S. Women From Japs

MANILA (AP) Two American women have reached Manila after dramatic rescues by guerilla troops under command of Col. Russel R. Volckmann, of Clinton, Iowa.

Mrs. Herman Kluge, of Schenectady, N.Y., was hidden by Ifugao tribesmen in the mountains of northern Luzon for 41 months while the Japanese searched for her with a price of 35,000 pesos ($18,500) on her head.

It is late 1945. Anna has endured her own harrowing ordeal, chased from village to village by Japanese intent on rounding up all resisters.

She is aware of the rumors about Herman’s fate. She’s told he was taken first to a prison camp and then to an underground dungeon called the icebox, where he is fed three handfuls of cooked rice a day and forced to drink the urine of Japanese soldiers.

“I still have hope that I will hear from him,” she writes to a relative in April 1945. “I can’t believe that he has left me for good. God only could protect him and I think He has.”

In August she writes, “Only hope he is alive and will be released when our boys get to Japan.”

In October, a soldier contacts Anna’s sister. He claims to have been with Kluge at a prison camp in Manila for a few weeks in September 1943.

“Captain Kluge was in good health and excellent spirits. Although he was confined to a cell, his treatment otherwise was good. Captain Kluge spent a good deal of time reading the New Testament.”

But by Feb. 1, 1946, Kluge is officially declared dead by the War Department.

“His service under my command in the Pacific War was characterized by his complete loyalty to our country,” Gen. MacArthur writes to the family. “In giving his life in this crusade for liberty, his name takes its place on the roll of our nation’s honored dead.”

Anna informs the alumni office of the grim news.

“I still had hopes to the very last that I would hear he was alive and they found him in some remote place.”

Waldron, secretary of the Graduate Council, sympathizes.

“It is always hard to have to give up hope but I know from what you have written and told me that you realize these hopes were slight. As one who knew Herman for many years and had a high regard for him, my sympathy goes out to you.”

Kluge is posthumously awarded the Purple Heart, Bronze Star and a presidential citation.

Anna is determined to keep her husband’s story alive. She writes a piece for the April 1947 issue of Union Alumnus magazine. It’s a precursor to a hefty manuscript written in longhand she completes in 1956 after returning to Englewood, Fla.

“But I won’t publish the book,” she tells a Florida magazine. “It is for my sons and their grandchildren that they may know what their father and grandfather stood for.”

She also provides a copy to the College for its archives. In December 1962, Anna passes away. She is 72.

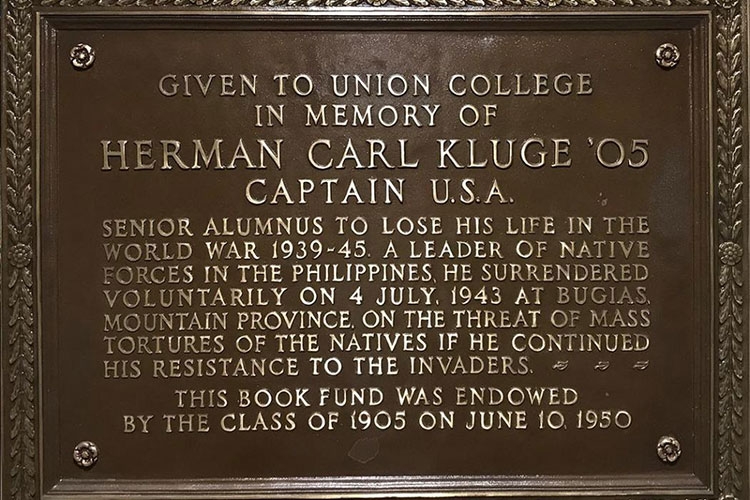

In June 1950, about a dozen members from Kluge’s Class of 1905 gather for its 45th ReUnion. To honor their fallen classmate, they establish a memorial fund to purchase books related to the Far East. They also commission a bronze plaque to be hung in the library.

“If you have ever wished to have a picture of how meager and futile an insignificant human speech can be when measured by a noble deed, you have that picture now,” Ernest Ellenwood tells the gathering, which includes Anna, family members and President Carter Davidson.

Ellenwood reminds his classmates of the words President Andrew Raymond spoke at their baccalaureate ceremony. Raymond told them that while life would be filled with discouragement and disillusionment, right and trust would always prevail.

“We find ourselves 45 years later discussing an achievement by our classmate, Herman Kluge, an achievement so spiritually inspiring, so far outside and above and beyond the petty concerns of everyday life that all of our discouragements and doubts become trivial and vanish like the mists of the morning.

“…The spirit never dies, and that right and truth and justice, as exemplified by Herman Kluge’s last great act of devotion, never perish.”

The Manila American Cemetery and Memorial holds the largest number of graves of the U.S. military dead of World War II, a total of 17,184. Most lost their lives in operations in New Guinea and the Philippines.

In the chapel near the center of the cemetery stand rectangular limestone piers inscribed with the Tablets of the Missing. Among the 36,286 names: Herman C. Kluge.

Herman C. Kluge ’63 never met the grandfather for whom he is named. He is born in 1940 while his grandparents are in the Philippines.

Family conflicts afford him little contact with his grandmother. As a young man, he familiarizes himself with the broad outlines of his namesake’s story through newspaper clippings and conversations with his father and uncles.

He is also reminded of his grandfather’s legacy when he goes to the library and sees the plaque hung a decade before his arrival at Union. Today, it’s barely visible, residing on a wall tucked in the third-floor hallway leading to the library’s administrative offices.

He’s often asked if he’s related to the honoree.

“Given to Union College in memory of Herman Carl Kluge, Captain U.S.A., senior alumnus to lose his life in the World War 1939-45. A leader of native forces in the Philippines, he surrendered voluntarily on 4 July, 1943 at Bugias Mountain Province, on the threat of mass torture of the natives if he continued his resistance to the invaders.”

Retired and living in Arizona, the grandson speaks matter-of-factly about his grandfather’s service.

“He did what he had to do,” he said recently. “He was a hero.”