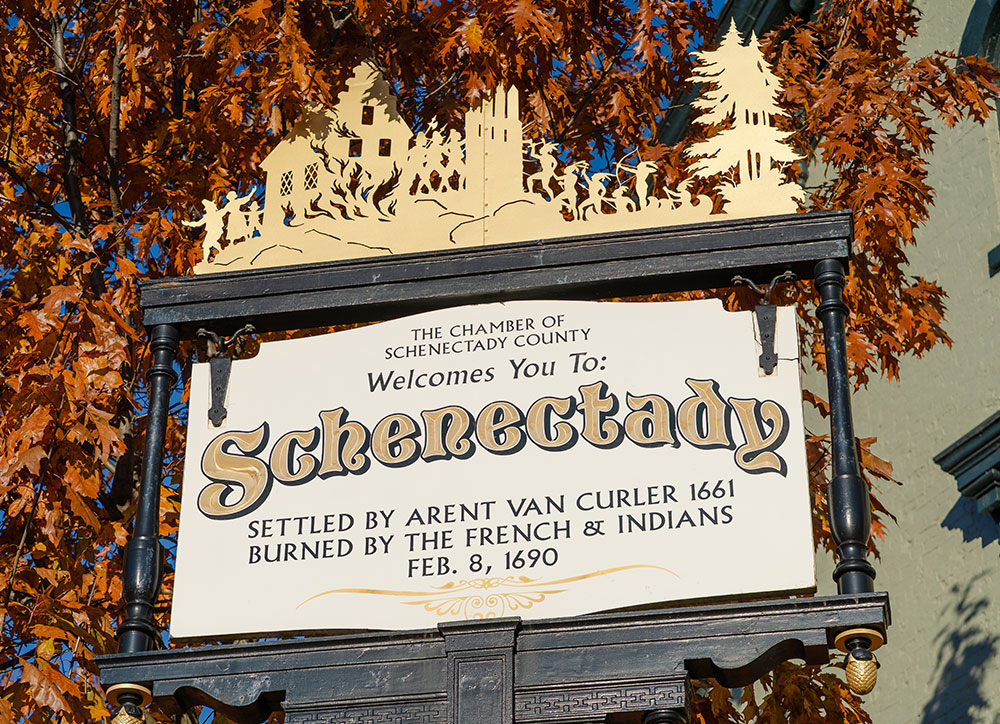

On the frigid, snowy night of Feb. 8, 1690, a band of French marauders and their Native American allies stormed the frontier village in what is now Schenectady, N.Y.

Sixty people were slaughtered during the brazen raid, including 10 women and 12 children, and dozens of others captured. The raiders set fire to most of the homes and barns in the community, leaving the settlement in ruins.

What came to be known as the Schenectady Massacre was one of the first skirmishes of King William’s War, a furious attempt to conquer New York and one of the most horrific yet obscure chapters in early state history.

New light is being shed on that dark chapter, thanks to a longstanding artifact in the College archives.

Consider: For decades, box 139 sat relatively undisturbed on a shelf along the back wall in the archive’s south stacks. Placed in the artifact collection, which includes sweaters, medals and other historic College mementoes, the small, archival box contains a rare archeological find -- a partial human skull believed to belong to a victim of the massacre.

Unearthed during an excavation in a downtown area in the 19th century, the skull was gifted to Union in 1877.

Now, 335 years after the massacre, the remains that rest delicately on tissue paper and serve as a grim reminder of one of the city’s darkest chapters are finally ready for a proper burial.

Working with representatives of nearby Vale Cemetery, which already contains some victims of the massacre, and First Reformed Church, the College will release the remains for a public internment in the spring. A plot and a small casket have been donated anonymously.

“I am happy we can finally lay her to rest,” said Sarah Schmidt, director of Special Collections and Archives at Schaffer Library. “She’s a human being and deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. She died at a time when there was no control over what happened to her body post-mortem. We now live in an age where you do have to consent to your body being used for science. She never did. It’s time to lay her to rest.”

The Schenectady Massacre has been the subject of books, plays, paintings and even a poem. Yet outside of the 518 area code, it remains a relatively obscure event in colonial American history.

The well-coordinated attack was part of a three-pronged invasion orchestrated by the governor of New France, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, on the English American colonial frontier after England had entered the war, said Kenneth Aslakson, associate professor of history. It was also in retaliation for the brutal English-backed Iroquois attacks in Canada that disrupted the lucrative fur trade.

“While dozens of scholarly works have been written about Bacon’s Rebellion (1676), King Phillip’s War (1675-76) and the Salem Witch Trials (1692), the Schenectady Massacre remains understudied,” said Aslakson.

Union’s connection to this historic event originated in 1842, when workers digging at the head of Maiden Lane (now Broadway), near State Street, uncovered several human skulls and bones, including the entire skeleton of a female with the face down.

“On the back part and entirely through the skull, was a cut, made apparently with a hatchet,” according to an account Aug. 19, 1942, in the Schenectady Reflector. “How long these bones may have been buried, or from what cause they may have been deposited there is left to conjecture.”

From there, the skull presumably ended up with Alexander Marselis Vedder, an 1833 graduate of Union and later a professor of anatomy and physiology at the College. At the time, it was not uncommon for human remains to be donated to colleges and universities for anatomical education.

Vedder gave the skull to his alma mater in 1877, a year before his death.

A handwritten paper label that stubbornly adhered to the skull hints at some of the provenance, though it’s not clear who wrote the note or when it became attached.

In any event, the College took possession of the skull, and except for rare occasions when it was removed from its alarmed, climate-controlled space to exhibit for students, it remained in a box, trapped in its history.

While visiting the historic Saratoga Battlefield in 2013, Frances Maloy, College librarian, learned that human remains from that battle were later often unearthed by farmers. A park ranger told her it was common practice to then re-inter the remains.

Maloy decided it was time to learn more about Union’s skull and prepare for a proper burial. She was also guided by a recommendation of the American Museum of Natural History, which states that the return of human remains is an “integral part of stewardship.”

The skull was subsequently loaned to the New York State Museum, where experts conducted an osteological analysis of the remains.

Their report concluded the skull likely belonged to a younger adult woman who suffered cranial trauma during a violent encounter. The woman sustained several sharp injuries, the report states, first being struck with a heavy-bladed instrument that penetrated the top of her skull and would have led her to collapse. Then while lying face down, she was struck in the back of the head multiple times with the same or a similar weapon, according to the report.

“The type of injuries exhibited in the skull are consistent with a brutal attack such as the one that occurred in Schenectady in 1690,” the report concludes.

A subsequent DNA analysis at the University of Binghamton in 2019 determined the skull was of European descent.

As the College inched closer to a burial for the remains, efforts were made to learn more about the victim. However, research by a project archivist for Schaffer Library was unable to determine the identity of the skull from among the list of 10 women killed in the massacre.

Meanwhile, Schmidt reached out to Vale Cemetery and the First Reformed Church, where officials agreed to help.

Plans call for a public ceremony in the spring to reinter the remains. The event will include the placement in the cemetery of the original headstone of a six-year-old boy killed in the massacre that has also been preserved in the College’s archives for at least a century.

“To actually be able to reinter even small remains from this era is both exciting and very moving as it is a very rare tangible remnant of that time,” said Paula Lemire, office administrator for Vale Cemetery. “We are looking forward to giving a dignified burial and final resting place to the skull of a young woman who must have experienced a terrible death over three centuries ago.”

In a 1940 radio address to mark the 250th anniversary of the massacre, Union President Dixon Ryan Fox offered listeners a searing account of the events that night.

“Amid the crash and shriek of the tumult and the roar of flames, women were struck down by arrow and tomahawk, little children brained at door posts and window jams,” Fox said on WGY-AM. “Scores of men, suddenly awakened, were hacked down in the same way…”

More than three centuries after the massacre, one victim is finally going home.