Fungi, with the exception of shiitake and certain other mushrooms, tend to be something we're disgusted by (think moldy bread or dank-smelling mildew). But they really deserve more respect, because some fungi have fantastic capabilities.

They can be grown, under certain circumstances, in almost any shape—from flip-flops (no joke!) to candle holders—and be totally biodegradable at the same time. And, if this weren't enough, they might have the potential to replace plastics one day. The secret is in the mycelia.

Biology Professor Steve Horton likens this mostly underground portion of fungi (the mushrooms that pop up are the reproductive structures) to a tiny biological chain of tubular cells.

"It's this linked chain of cells that's able to communicate with the outside world, to sense what's there in terms of food and light and moisture," he said. "Mycelia take in nutrients from available materials like wood and use them as food, and the fungus is able to grow as a result."

"When you think of fungi and their mycelia, their function—ecologically—is really vital in degrading and breaking things down," Horton added. "Without fungi, and bacteria, we'd be I don't know how many meters deep in waste, both plant matter and animal tissue."

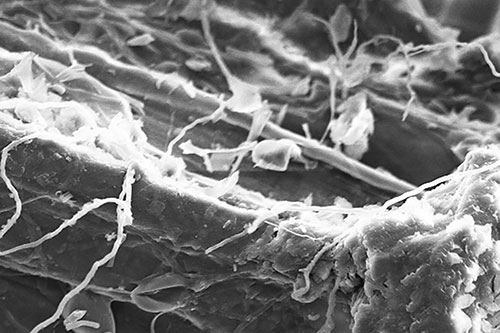

Looking something like extremely delicate, white dental floss, mycelia grow in, through and around just about any organic substrate. Whether it's leaves or mulch, mycelia digest these natural materials and bind everything together in a cohesive mat. And these mats can be grown in molds, molds that might make a shoe sole or packing carton.

Ecovative Design, in Green Island, N.Y., is the only company harnessing this particular mycological power right now. And it has Horton, and another Union researcher, Ronald Bucinell, to help it do so.

Ecovative basics

Founded by Gavin McIntyre and Eben Bayer the same year they graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Ecovative has been in business since 2007. The company uses several species of fungi, which differ markedly from those sold in grocery stores, to manufacture environmentally-friendly products.

"Most of our partnerships are secret, but we just partnered with the Sealed Air Corporation (the inventors of bubble wrap) to expand distribution of our protective packaging products," said McIntyre, who is chief scientist. "These are already used by the likes of Dell and Crate & Barrel, and we're also in the early stages of designing a compostable shoe with one of the world's leading sports apparel manufacturers. We have development projects in everything from floral foams (think flower arrangements) to automotive components too."

Making these items is relatively straightforward, at least in some respects, because the fungi do most of the work.

The process starts with farming byproducts, like cotton gin waste; seed hulls from rice, buckwheat and oats; hemp or other plant materials. These are sterilized, mixed with nutrients and chilled, Ecovative's Director of First Impressions Kristen Renaud explained. Then the mycelia spawn are added and the whole amalgam is put in a large container. Dozens of such containers are held in vertical racks as the mycelia grow, quickly turning the entire package a milky white as the fungus permeates every available cranny of space and substrate.

The mycelia are so good at proliferating, in fact, McIntyre said, that every cubic inch of material contains eight miles of the tiny fungal fibers.

Next, this lengthy—but compact—matrix is removed from the container and placed in a mold the shape of what-ever item Ecovative is making. Once the desired texture, rigidity and other characteristics of the product are achieved, it's popped from its mold and heated and dried to kill the mycelia and stop its growth. Drying also eliminates any potential allergens that may be present.

"Our all-natural products, the creation of which takes less than five days, have no allergy concerns and are completely non-toxic. They could be eaten, though they're obviously not meant for consumption," Renaud said, laughing, "and they wouldn't taste very good."

More impressive is the fact that they're also impervious to fire (to a point), and as water resistant as Styrofoam, but they won't sit around taking up space in a landfill.

"Our materials are all Class I fire walls, because the fungal cell wall is very robust and water insoluble, and the rice hulls and other waste we use have naturally high silica content," McIntyre said. "This means they can be hit with a blow torch and not burn."

"They are also more UV-stable than foam since they are not petrochemical-based, and won't emit volatile organic compounds," he added. "When exposed to the right microbes, they will break down in 180 days in any landfill or backyard."

Mycelium is comparatively inexpensive too.

Using farm garbage that can't be fed to animals or burned for fuel, Ecovative gets a good deal on the plant matter its mycelia grow on. Better yet, the fungi the company use can be propagated without sunlight or much human oversight in simple trays at room temperature— no immense greenhouses with costly temperature-control systems needed.

And that, of course, helps with the utility bills. It also means a smaller carbon footprint.

"Today, our products require a tenth of the energy and emit an eight of the carbon dioxide of traditional foams like expanded poly-propylene," McIntyre said.

He and Bayer, the company's CEO, hope to get their business to the point where they can displace all plastics and foams in the market.

"Ten percent of all our petroleum is allocated to the production of plastics and foams. It's a valuable resource not well-spent on cups that are discarded after one use," McIntyre said. "We want to grow a sustainable business not dependent on a resource that will be gone in less than a century."

Union professors and researchers Steve Horton and Ronald Bucinell are aiding them in this effort.

Union R&D

Horton got involved with Ecovative about a year ago when Computer Science Instructor Lance Spallholz '69 - who Horton describes as an "uber hockey fan" - sent him a link to a local company that works with fungi.

"I looked at their website and saw this little bit that said, ‘Contact us,'" Horton said. "Normally I wouldn't have, but I did and that very night at 11:30 I got a response from Gavin. He said they'd been looking for a partnership like this."

"So all this really started with hockey," he added, laughing. "Lance is a big fan, so are Gavin and Ron, we all are."

In Horton's lab, he and his students are tinkering with a species of fungus Ecovative uses in its manufacturing.

"We manipulate one strain in various ways to see if we can make versions of the fungus to suit certain applications the company has in mind," Horton said. "For example, it might be helpful if Ecovative has certain versions that grow faster."

"We're also trying to learn more about the fundamental biology of the organism," he added. "All sorts of things are possible, and those possibilities will only increase as our knowledge increases."

McIntyre agrees.

"As a geneticist, Steve has unique experience working with higher-level fungi," he said. "His ability to help us understand some of the genetic pathways that allow our fungal species to behave the way they do is extremely important."

Collaborating with RPI's Daniel Walczyk, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Ronald Bucinell and his students also offer critical support to Ecovative's research and development pipeline. Bucinell's particular expertise is in experimental mechanics and the mechanics of reinforced materials.

"Different industries have different requirements for things they use," said Mickey Allan '14, a mechanical engineering major who conducted summer research on Ecovative's products. "So we test sample material from the company to see how strong it is under different parameters. Do mycelia bind better to this plant material or that one? Does the way it's treated—with heat or something else—make it stronger or weaker?"

As Allan was talking, he and Bucinell were working with a sample Ecovative hopes to use in cars to insulate and absorb sound.

"Since 2010, Ron has supported the development of some of our structural composites for the auto and construction industries," McIntyre said. "His laboratory tests many of our new materials, assisting in the development and improvement of our material blends."

"Some of our applications also include biodegradable flip-flops," Bucinell added. "Tourists leaving flip-flops behind at Caribbean resorts is a major problem, the landfills down there are filled with them."

Whether its footwear or fundamental genetics, the Ecovative founders are grateful for their higher ed partners.

"Steve is unique because his research over the last 28 years has focused on the effect of genetic pathways on fungal physiology, which factors greatly into what we can do with mycelia," McIntyre said. "And Ron is one of the foremost experts in composites design. To have these two scientists so close to our facilities in Green Island is highly valuable."

"This is a brand new field in materials, and collaboration allows us to learn a lot, and quickly," he continued. "That's really important when you're trying to replace plastics."

It's also really important to Union, its students and the larger community.

Union and beyond

Integral players in Ecovative's innovative business model, collegiate partners have contributed to the company's achievements and impressive growth.

In just the last two years, Renaud said, the company has doubled in size, both in terms of physical space and payroll. It employs 50 people, from engineers and biologists to sales staff.

"Our relationship with Ecovative is an excellent example of how Union supports the economic development efforts in the greater Capital District," Bucinell said. "We have also successfully collaborated with Ecovative and RPI on grants from NSF and NYSERDA, enhancing college-company partnerships across the region."

It's also heightened interest in Horton's lab.

"I've generally been able to get students engaged with our projects, but this is a whole new dimension," he said. "The applied aspect— that their work actually gets utilized in industry—really appeals to them. So does the nature of this business, which is very eco-friendly as opposed to exploiting the environment in a non-renewable way."

In a similar vein, Bucinell credits the Ecovative - Union partnership with providing summer research, internship and employment opportunities for students.

Kyle Bucklin '12 was hired by the Green Island company last June. A mechanical engineering major, he worked in the machine shop during his days at Union. Having learned to custom-make machine parts, like those for the College's competition-grade Baja car, Bucklin carries out his responsibilities at Ecovative with confidence.

"I work in the shop to help produce raw material, stream-line the company's waste stream or design parts for our machines," he said. "Everything's very specific to what we do; we can't really go out and buy it. We make it ourselves."

Bucklin enjoys his job immensely, and is particularly proud of his Union degree.

"Many of the engineers I work with have great degrees [from other colleges]," Bucklin said. "But I can keep pace with them, and I think my background, which also has a good deal of liberal arts, is especially valuable. It helps me interact with people outside the company to get materials I need. It helps me communicate."

He also values his relationship with Bucinell, and in turn, Bucinell's relationship with McIntyre and Bayer.

"Union has professors with close ties to area businesses, and that's incredibly important. Professor Bucinell was able to look at me and say, ‘You'd be a good fit for this company, why don't you check it out?'" Bucklin said. "So I did, and I am a good fit. I love it here."

"It's totally worth it to come to work every day and do things no one else in the world is doing—and to help the world," he continued. "This is the perfect place for me."