In 1940, as Nazi Germany advanced across Western Europe, the New York State Legislature convened a committee. The goal: to identify and root out those in the state university system suspected of having Communist ties.

Known as the Rapp-Coudert Committee, the body held a series of private and public hearings for nearly two years in which hundreds of educators were interrogated, threatened and in many cases, fired, for their alleged radical connections.

The committee’s work is often referred to as a prelude to McCarthyism.

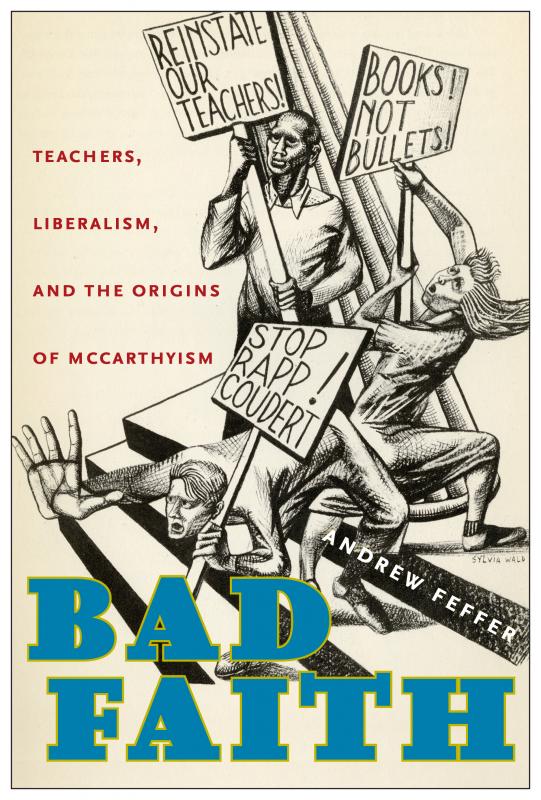

Andrew Feffer, professor of history, has done extensive research on the committee and its chilling impact on academic freedom. His book, “Bad Faith: Teachers, Liberalism, and the Origins of McCarthyism,” was published this month by Fordham University Press.

Feffer joined Union in 1989.

How did you choose this topic for a book?

I was working on another project that brought me to the huge Rapp-Coudert archive that is part of the New York State Police Non-criminal Investigations collection at the New York State Archives in Albany. The Coudert probe was also directly related to other work I had done on the philosopher and democratic theorist, John Dewey, who comes out looking rather less democratic in this study than he would have liked. I also have long been interested in the history of the left in the U.S., including the repression of left-wing dissent, whether during the McCarthy period or earlier. It is a history that is especially relevant today.

What does "Bad Faith" in the title refer to?

In the early 1930s, liberals and social democrats under Dewey's tutelage, people who had entered politics during the Progressive Era (1890s-WWI), began accusing younger, radical socialists and communists (who were largely inspired by the 1917 Russian Revolution) of "misrepresenting" their motives as they participated in the governance of unions and other progressive organizations. The notion was that these young communists actually wanted to hijack those organizations and use them to promote "class war," foment revolution and overthrow the American government. This was the "bad faith" with which the communist left, it was argued, participated in democratic institutions and the nation's democratic way of life. The term also refers to the way many liberals misrepresent themselves as champions of democracy, yet engage in witch-hunts like Rapp-Coudert that attack communists and accused communists for rocking the boat.

Historians have called Rapp-Coudert a “prelude to McCarthyism.”

In some sense, it was a prelude to McCarthyism. But the point of the book is to show that anti-communism, including liberal anti-communism, had much deeper roots in American political life and culture. The book traces the Rapp-Coudert episode back to the early 1930s, to conflicts in the New York City locals of the AFT, between liberals and social democrats, on the one hand, and young communist teachers, on the other. The disagreements largely involved differences over how to best advance public schooling and the interests of public school teachers during the Depression. A lot of this disagreement had to do with how aggressively and publicly teachers would push city and state government to fund and restore Depression-era cuts to public education. The liberals and social democrats wanted "responsible" negotiations with city and state authorities. The communists wanted a more confrontational approach involving public demonstrations and "mass actions" to pressure government officials.

Many teachers and staff lost their jobs after being "exposed" as communists. Any particular story stand out?

The story of Alice Citron, who in 1950 lost her job teaching in Harlem as a consequence in large part of the Rapp-Coudert probe. She was one of several teachers who helped start Black History Week in New York City and led a campaign in the mid-1930s to replace racist history and geography texts that had been widely used in the city's schools. The author of one of those texts, a school administrator, by 1950 had advanced to become superintendent of schools. It was he who fired Citron. Citron's campaign to teach a more inclusive version of history and geography had a profound influence on Harlem students, including a young James Baldwin, who recounted on a number of occasions the experience of having to read racist versions of his own history as a child. Citron's work, and the work of her collaborators, were set back by the wave of anti-communism. Their work would not recover until the 1960s.

What do you want the takeaway to be for the reader?

That by purging American schools of communists and the communist tradition, McCarthyism in general, and the Rapp-Coudert inquisition in particular, impoverished American intellectual life and political culture, seriously compromising our ability to achieve a real democracy.

Are there any lessons in Rapp-Coudert that are relevant today?

Yes. When young political leaders like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez come to the forefront of a new socialist movement, we should recognize a truly democratic opportunity in her and others' engagement of class politics.

One of the lessons of the book is that it wasn't just conservatives who created McCarthyism but liberals as well -- people like Dewey. We are entering into a new era of class politics, animated by levels of economic inequality not seen since the 1920s and reinforced by the indifference and greed of current political leaders, especially in the Republican Party. Under those circumstances we should be prepared for attacks on the entirely reasonable socialism of an Ocasio-Cortez, not only from conservatives and the extreme right, but also from liberals who still think that by placating Wall Street they can reboot an economy in which a "rising tide will raise all boats." I think quite a few reasonable people have lost faith in that liberal vision. But there remain many leaders who will use any means necessary, including a new McCarthyism (and collusion with a foreign power) to purge those critical and dissenting voices from American political life.