Perhaps no change at Union was more transformative than welcoming women.

There is little in our historical record to suggest that Union’s decision to admit women as full-time students in 1970 was the result of some kind of progressive wave.

Rather, coeducation was a matter of survival.

By the end of the 1960’s, most long-established men’s colleges had announced plans or begun to admit women. Union’s leadership was concerned that the College would become “exclusive.”

The 1967-68 edition of The Gourman Report, though criticized as an unreliable ranking instrument, gave at least a sense of the higher education landscape. Of the 1,187 institutions in the U.S., 919 were coeducational, 175 exclusively for women, and only 93 exclusively for men.

“Coeducation ... is neither a new phenomenon, nor a radical experiment,” wrote Samuel B. Fortenbaugh ’23, chair of the board, in a May 1969 letter to alumni. “In point of fact, it is already the dominant form of American higher education, and during the next decade it will almost certainly become the pervasive one.

“To put the matter bluntly,” he continued, “the market for same-sex colleges is shriveling. The college seeking a healthy future cannot ignore that fact.”

The deliberations

In his 1967-68 annual report, President Harold Martin wrote, “[Coeducation] might have been raised by any part of the college constituency—alumni, trustees, faculty or students—and it has indeed been raised by some members of each from time to time over recent years.

“The most vociferous argument has, of course, come from students, usually through the college news- paper but sometimes from various student groups, in favor of a change or opposed. But the steadiest pressing of the issue has come from the faculty ...”

In 1967, a “July Committee” of faculty recommended coeducation. The next year, Martin appointed an ad hoc committee with Prof. Carl Niemeyer of English as chair. Other members were Prof. Henry Butzel of Biology; Prof. Charles Gati of Political Science, Prof. Filadelfo Panlilio of Mechanical Engineering, Prof. Mira Wilkins, of Economics and History (the lone woman); and Bernard R. Carman, director of public relations and College editor.

"COEDUCATION ... IS NEITHER A NEW PHENOMENON, NOR A RADICAL EXPERIMENT. IN POINT OF FACT, IT IS ALREADY THE DOMINANT FORM OF AMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION, AND DURING THE NEXT DECADE IT WILL ALMOST CERTAINLY BECOME THE PERVASIVE ONE."

–Samuel B. Fortenbaugh ’23, chair of the board, May 1969

Niemeyer’s appointment as chair “may enrage the young,” Martin wrote in his annual report. “I knew him to be skeptical about coeducation and I thought it the better part of prudence and proper respect to the tradition of the College to weight the committee, if at all, toward the status quo,” Martin said, adding that he did not attempt to determine the leanings of other committee members. He later learned that “the original weight of committee sentiment fell on the side of skepticism,” he wrote.

James Underwood, professor emeritus of political science who arrived on campus in 1963, recalled Martin as one of the only people on campus who were reluctant about coeducation. He recalls Niemeyer as conservative but open enough to

have weighed the options. Under- wood also recalls Niemeyer chastising the president for his membership in the Mohawk Club, then a men’s-only organization.

Deliberations in 1968 relied heavily on work already under way at Princeton, which had surveyed 4,680 high school seniors and found that single-sex liberal arts schools were the least popular option. The survey also found that weaker students preferred single- sex colleges. “The Princeton survey yields one message, loudly and clearly,” wrote editor Bernard R. Carman in a 1968 commentary. “The College that remains segregated will sooner or later be hurting for students.”

The committee hosted Prof. Gardner Patterson, chair of the Princeton committee, to discuss among other things the optimum size of the new student body. Women should be added in meaningful numbers, in a ratio of at least one-fifth of the total, according to the committee report. The final recommendation was a student body of 1,200 men and 400 women.

An impact on science and engineering?

The committee was highly concerned about the effect coeducation could have on science and engineering. The committee report assumed that “women systematically take different kinds of courses, and major in different subjects than do men.” And even more jarring: “It may also be noted that women, regardless of innate intellectual abilities, lead different lives from men. For many of them marriage is a career, as it is not for men.”

Deliberations also brought up the question of replacement versus expansion, either option having costs. Replacement, some assumed, would drain enrollment from the sciences (except perhaps biology) and engineering. “The female of the species has a positive aversion to chemistry, physics and, of course, engineering in all its forms,” Carman wrote. The committee estimated that expansion would run about $7 million, perhaps dictating cuts in areas least attractive to women: science and technology.

Committee members also assumed that the 3 to 1 male-female ratio would not last, according to Carman. The population of college- bound men “cuts to much lower intellectual and socioeconomic levels” than women, Carman wrote. If it is easier to recruit qualified women, he surmised, the male- female ration would drift toward parity, “to the peril of science and engineering.”

“In the end, it may well be that the strongest arguments in favor of coeducation are those we may list under the broad heading of consumer demand,” Carman wrote. “In an age when the most intelligent and articulate of students decry the irrelevance of much of their education, how long can a college ignore one of the central facts of modern American life, association of the sexes on the basis of equality?”

The alumni speak

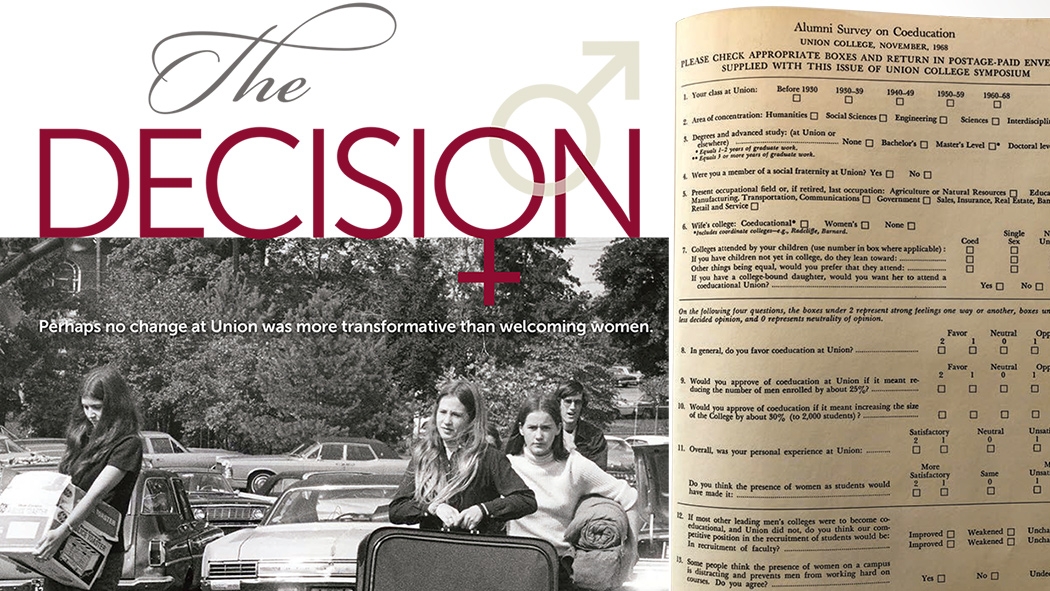

In a survey in the winter of 1968, alumni recorded themselves in favor of admitting women by a margin of nearly two to one. Of the 2,521 surveys returned, 1,517 (60 percent) registered moderate or strong approval; another 813 (32 percent) indicated moderate or strong opposition.

Pre-1930 alumni were the only group in which the majority opposed coeducation. One member produced a rare comment: “Damn you, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Look at the ruin and devastation you have caused. Poor Union. A once venerable and righteous institution has bitten the dust ...” The response was not signed.

The survey confirmed one important projection from the Princeton study that was echoed by the Union committee: college- bound students prefer coeducation. Indeed, 64 percent of alumni said they would want a daughter to attend a coed Union.

In comments that came back from the survey, only 27 respondents used financial support (of lack thereof) to reinforce their position. A total of six alumni said they would support Union regardless.

The comments also revealed that a large number of alumni supporting women’s admission at Union had attended coeducational graduate programs where, according to an editor’s comment in the summer 1969 Union College Symposium, they had “discovered to their delight that women can do more than decorate a fraternity party.” The alumni publication reported that the College discounted a few of the surveys that it determined had been completed by wives of alumni.

However, surveys were counted from the handful of alumnae who had earlier completed their degrees through the evening division. “They produced a rare note of unanimity in the statistics,” the alumni editor wrote: “to a man, the ladies believe in coeducation.”

The students speak

While there is no record of a student survey, an Oct. 1, 1968, Concordiensis editorial may have summarized student sentiment:

Union will become coed, or Union will become exclusive and will deal with a dwindling number of applicants who desire a highly scientific, specialized and expensive kind of education.”

The seven-day presence of women on the campus will create, if not a more organic, dynamic, sensitive and diverse atmosphere, then at least a more healthful one.

Concordiensis fully agrees with the faculty committee’s opinion that “a more normal kind of relationship between the sexes, based on a range of shared experiences broader than an hour of deafening rock and a communally broached keg of beer, can only be beneficial.”

Because Concordiensis is concerned about Union’s retention of not only its present status, but also its viability, we endorse the recommendations of the faculty committee and urge all students to demonstrate their concern by similarly supporting the Union of the future, not the Union of the present.

Union was one of the first colleges in the world to tolerate all religions. Let us not allow Union to be one of the last to discriminate on the basis of sex.

The decision

In September 1968, Union’s faculty voted in favor of coeducation, with one dissenting vote, followed by the Board of Trustees’ affirmation to admit women starting in September 1970.

Once the decision was made, the College renovated North College and Richmond House for women and, to make more room, increased the number of men allowed off-campus housing.

With preparations under way, Martin told the trustees, “I suspect that the wisest course is to think in terms of some extra human beings more than in terms of a second sex of students except for such elementary considerations as ironing boards, increased closet space and full-length mirrors.”

[For more, see the “Women at Union” entry by Faye Dudden in Encyclopedia of Union College History, Wayne Somers, ed.]