Nearly everyone at some point in life will have a disease that requires surgery, the manual art of healing. But little is known about the history of surgery.

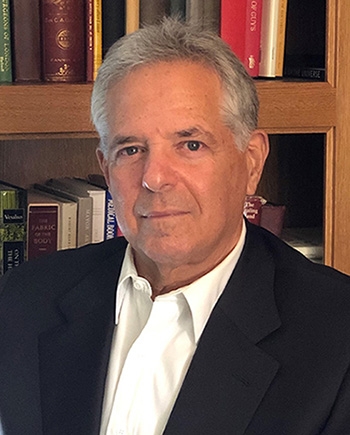

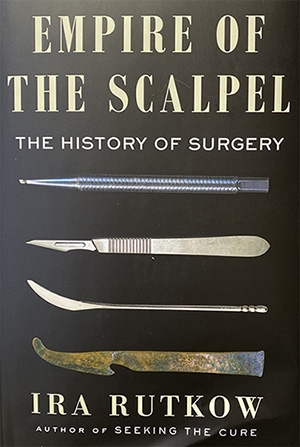

Enter Dr. Ira Rutkow ’70, surgeon-turned-surgical historian. His latest book, Empire of the Scalpel: The History of Surgery, traces the evolution of the seemingly routine operations that so many of us take for granted.

Over the past 5,000 years of recorded surgery, success has required an understanding of anatomy, the ability to control bleeding, anesthesia and antisepsis. Rutkow describes early surgery as a series of blunders and breakthroughs, with success never guaranteed. Many advances were made during wars, when physicians had to improvise.

Most writing about surgery covers the drama of the operating room, Rutkow notes. Throughout 50 years of training and practice, Rutkow was dismayed that many patients had little understanding of medical training, licensure or specialization. More perplexing, he found, was that surgeons had little understanding of the basic history of their field, when anesthesia was invented, for example.

Rutkow realized his true calling – writing – only three years into his 11 years of medical training.

“The writing bug caught me in my junior year of medical school,” he said. “I always wanted to write more than I wanted to operate.

“I was more interested in the gestalt of the surgical world: the sociology, the politics, the history, the anthropology, what makes a surgeon a surgeon,” he said.

But to write about surgery and have credibility, he felt he had to become a surgeon.

He stayed the course with his medical training all the way to a residency in general surgery. At the same time, he took a fellowship in medical economics at Johns Hopkins and earned a Ph.D. in public health.

During this fellowship, Rutkow learned that hernia repair was among the most common surgeries. It is also elective with virtually no emergencies.

In the mid-80s, Rutkow began a hernias-only practice along with an ambitious advertising campaign that drew the ire of his contemporaries. Medical advertising, he notes, is commonplace today.

“I became a hernias-only surgeon, not because I love doing hernias, though I do,” he said. “But it allowed me to manage my time.”

Rutkow has authored eight books, most on medical history.

He opens Empire of the Scalpel by describing an experience that sparked his interest in surgical history. As a young intern, a patient with a seemingly minor head injury had a sudden decline. Panicked and fearing he had missed earlier signs, Rutkow rushed to tell an attending doctor. Once in the operating room, the patient was saved with a trephination, drilling into the skull to relieve the pressure of an intracranial bleed.

Afterward, a senior neurosurgeon pulled Rutkow aside to assure the shaken intern that his response had saved the patient. He also explained that the trephination was among the earliest known operations; cavemen chiseled holes in skulls to release evil spirits. “The elegance and simplicity of his observation would define and guide my career,” Rutkow writes.

Despite Rutkow’s claim that “a liberal arts education gives you the widest background that you can incorporate into becoming a person and a doctor,” there is little in his Union transcript to show that he strayed far from biology.

He knew the names of the most popular professors in social sciences – Joe Board, Bob Sharlet, Malcolm Willison – but he never took their classes.

“Looking back, I was too much of a pre-med,” he recalls. “I never took a course in history or sociology or political science. I was pure pre-med. Go to medical school. Become a doctor. That’s the way it was in the 60s.”

At 17, Rutkow arrived at Union when strict rules – including parietals – were enforced. Though the rules had eased by the time he graduated, Rutkow feared that a transgression could threaten a letter of recommendation to medical school.

“I was a very good student,” he said. “I followed the rules.”

So did his friends. Over a dozen members of his fraternity, Phi Epsilon Pi, who graduated in 1970 went on to become doctors.

Rutkow regards same-day and minimal access surgery among the greatest innovations of modern surgery. “Patients can have an epidural and hernia surgery and be home in two or three hours and back to work in a week.”

He said he expects progress will continue in robotics, artificial intelligence and transplants.

Modern surgery has been around for about a century, Rutkow observes, and what qualified for surgery before that would be unrecognizable today.

So, it is important to consider frames of reference. “People talk about barbaric treatments, torture, malpractice of the 19th century and earlier, but what they were doing was state of the art,” he said.

“I would like to think that 200 years from now, physicians and surgeons will not look back at what we were doing in 2022 and think, ‘What were those people doing? That was barbaric. Whoever heard of chemotherapy? What were they doing with antibiotics?’ Instead, they should realize that what we were doing was state of the art.”