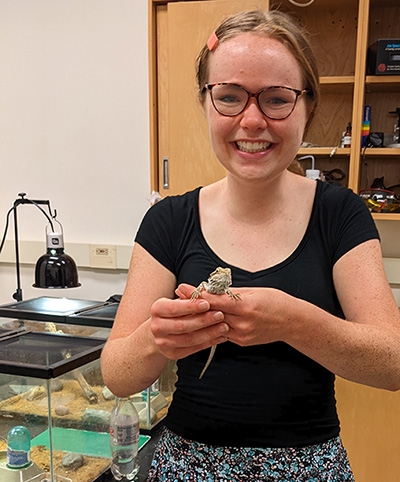

Caitlin Williams ’23 has some dynamic lab mates.

“They each have their own personalities. Frances was looking at us – paying close attention this whole time – while Bruce and Buzzy were mostly ignoring us and doing their own thing,” she said during a recent interview. “I didn’t expect this when I started working with them.”

Why not?

Because Frances, Bruce and Buzzy aren’t people. They’re bearded dragons.

Williams and her advisor, Leo Fleishman, have been working with these lizards, which are native to Australia, since spring 2022. (Though these three were captive-bred and purchased at pet stores).

They want to know what bearded dragons are capable of learning and how they perceive (literally see) the world.

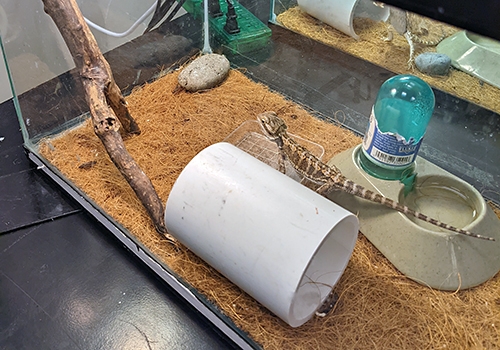

To begin to learn about their cognitive capabilities and vision, they built a Y-maze. It’s basically a box with an open area at one end and two choices (divided by a little wall) at the other end. The two choices, in this case, were red or blue dots.

Since Buzzy only joined the trio in June, it was just Frances and Bruce who participated in this first iteration of the experiment.

“I would put Frances or Bruce in the maze, and then after five minutes passed, I’d put a worm in front of one of the colors,” Williams said. “After about four weeks, Frances learned to go to red dot before the worm went in. It took Bruce a little longer to learn to go to the blue dot.”

Even so, bearded dragons can apparently differentiate blue from red – and associate a particular color with treats. Which allowed Williams and Fleishman to add another layer to their research.

“Now that we know they can learn, we can start asking more questions about what they can learn,” Fleishman said. “Over the summer we studied their ability to perceive spatial orientation.”

In the same Y-maze, two sets of black and white stripes replaced the colored dots. All three lizards could now choose between horizontal stripes or vertical stripes.

Williams witnessed a similar pattern of learning with this experiment. Frances and Buzzy both learned to associate specific stripe patterns with treats. Bruce failed to do so, but there could be several explanations for this.

Perhaps Frances and Buzzy are just quicker on the uptake. Or maybe they’re more relaxed around people.

“Frances is much more comfortable with being handled,” said Williams. “Bruce is more frightened in general.”

“Fear level has a big impact on learning,” Fleishman added. “But this is why we went with pets. There are advantages to animals that are used to being held. We couldn’t do this with wild lizards; they’d be too frightened to show us what they can do.”

Since Frances and Buzzy are able to tell horizontal stripes from vertical stripes – and understand that a treat is associated with one or the other – Fleishman and Williams are now testing with polarized light.

While the experiment is ongoing, early results indicate the lizards can indeed see polarized light – something humans can’t do.

“I like the idea of figuring out what animals can perceive. So many animals see a much broader range of light and color than we do,” Fleishman said. “Understanding their capabilities gives a richer, more interesting view of the world.”